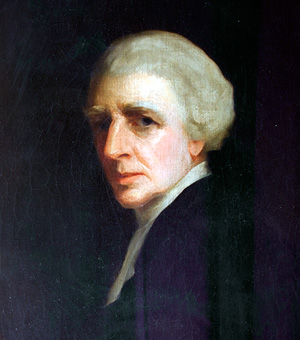

Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh

Queen’s College President, 1786 to 1790

Upon the death of Frelinghuysen in 1754, Hardenbergh took over the parish of his preceptor and assumed an active role in establishing a Dutch college. In 1763 he traveled to Europe to renew the cause for church independence and to inform the Amsterdam church of efforts in the colonies to appeal to King George III of England on behalf of the college movement. His efforts were partially rewarded when on November 10, 1766, William Franklin, governor of New Jersey, granted a charter for Queen’s College.

When the Queen’s College Board of Trustees convened for its first meeting in May 1767, Hardenbergh took his place alongside other Dutch ministers who had been active in its founding. Launching the new college proved to be difficult, taking five years before opening at the Sign of the Red Lion, a former tavern located on the corner of Albany and Neilson streets in New Brunswick, which housed the students of the college and the grammar school. In November 1771, Frederick Frelinghuysen (son of the late John Frelinghuysen) commenced instruction for the first students.

The college went for more than a decade without a president, during which time governance remained in the hands of the trustees. The college grew slowly over the next few years, and by 1774, when the first commencement was held, there were over 20 students enrolled. Hardenbergh, staunch and dedicated proponent of Queen’s College, presided over the memorable event and conferred on behalf of the trustees the first and only degree of the day to Matthew Leydt.

Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh was an outspoken proponent for American independence who “took no pains to conceal his opinions” and frequently “stirred up the people through the pulpit ministrations.”

As the Revolution approached, Hardenbergh became an outspoken proponent for American independence. According to one writer, he “took no pains to conceal his opinions” and frequently “stirred up the people through the pulpit ministrations.” He was a delegate to the last Provincial Congress, which met in Burlington in June 1776 to ratify the Declaration of Independence and frame the constitution of the State of New Jersey. He served several terms in the General Assembly, where his colleagues “testified their confidence in his political wisdom and patriotism.”

In 1781 Hardenbergh left New Jersey to return to Ulster County, where he was to remain for five years as pastor of the Reformed Churches. He stayed active in the college’s affairs, seldom missing a meeting of the trustees. Meanwhile, the trustees continued their search for a president with the assistance of a reunited and autonomous Dutch Church. In 1786 the trustees appointed the Reverend Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh as the first president of Queen’s College.

Queen’s College prospered during the next four years under the leadership of Hardenbergh. With assistance from the trustees and ministers in the area of New Brunswick, he campaigned for additional subscriptions to meet expenses and paved the way for attracting funds to erect a new home for the college. Enrollment climbed slowly, and by 1789 the graduating class of the college included 10 students. Hardenbergh reported to the church synod that year on the progress of the institution but also cautioned that more was needed in the way of financial support. But before the churches could come to the college’s aid, President Hardenbergh succumbed to tuberculosis and died on October 30, 1790.

Queen’s College had lost its most loyal friend and avid supporter. Described as “a grave and dignified man,” Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh was regarded by his contemporaries as one of the “distinguished lights of the profession.” Selected on four different occasions as president of the General Synod of the Reformed Church, his devotion and dedication were highly praised by the Dutch clergy.

This biographical sketch was authored by Thomas J. Frusciano, Rutgers University Archivist. It originally appeared in The Journal of the Rutgers University Libraries.